ICE looks to expand its reliance on the 287(g) program

A cluster of DHS procurements shows a push toward mass case triage and expanded police deputization.

A set of DHS contracting documents published over the past month outline a significant expansion of immigration enforcement capacity. The documents, mostly framed as routine requests for professional support services, describe plans to increase intelligence gathering, accelerate case processing, and coordinate apprehensions with state and local police.

A National Coordination Hub

ICE recently released a request for information for a new 287(g) National Call Center near Nashville, Tennessee. While the document describes operational support requirements, it also details plans for DHS to increase intelligence gathering, accelerate case processing, and coordinate mass apprehensions with state and local police.

The proposed call center would operate around the clock and support more than a thousand 287(g) partner agencies. A 287(g) partner is a local law enforcement office that has signed an agreement allowing its officers to perform certain federal immigration enforcement functions. These arrangements effectively create a distributed network of local police who can run immigration checks, issue detainers, and escalate cases to ICE.

The emphasis on 287(g) partnerships may reflect ICE’s ongoing struggle to meet its own staffing goals. Congress allocated $30 billion for ICE to hire 10,000 new officers by the end of 2025, which would more than double the agency’s enforcement workforce. But the hiring push has faced significant problems. More than one third of recruits have failed basic fitness tests, and White House border czar Tom Homan acknowledged a “high fail rate” on physical standards. ICE has dismissed more than 200 new recruits while they were in training for falling short of hiring requirements, including criminal backgrounds and failed drug tests.

Former acting ICE director John Sandweg predicted the agency won’t see a significant increase in street-level agents for three years, which would place any meaningful staffing gains at the end of the current administration. The agency waived age requirements in August, now accepting applicants as young as 18 and with no upper age limit. Historical success rates suggest ICE may need more than 500,000 applicants to achieve a net increase of 10,000 officers.

Against that backdrop, the 287(g) call center provides a workaround. Instead of waiting years to train federal agents, ICE could — in practice — immediately tap into a network of local police who are already trained, armed, and embedded in communities nationwide.

According to the Performance Work Statement, contractors will run queries across criminal and immigration databases, prepare enforcement packages, and advise police officers during encounters involving non-citizens. The center will have access to ServiceNow based case tracking, national databases, and ICE systems that interface with the non detained docket. The staffing levels, the twenty four hour posture, and the requirement for surge capacity all indicate an operation built for higher volume than what currently exists.

Targeting Unaccompanied Children

The most striking section is Task 2. ICE directs the contractor to create a strategy that uses 287(g) resources to locate unaccompanied children. Unaccompanied children, or UACs, are minors who cross the border without a parent or legal guardian and are placed with sponsors while their immigration cases proceed. Task 2 calls for mining federal, state, and local databases to produce “targeting packages” that are then sent to law enforcement partners.

The administration launched this effort publicly in November as the UAC Safety Verification Initiative, framing it as a correction to Biden-era policies. The press release emphasizes child exploitation and criminal sponsors:

“This new law enforcement partnership, known as the UAC Safety Verification Initiative, represents ICE’s commitment to protect vulnerable children from sexual abuse and exploitation through collaboration with 287(g) law enforcement partners.”

DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin blamed the previous administration directly, stating that “many of the children who came across the border unaccompanied were allowed to be placed with sponsors who were smugglers and sex traffickers.” The release provides a list of criminal sponsors arrested in various states, including cases involving rape, human trafficking, and possession of child sexual abuse material.

The framing positions the initiative as a rescue operation. The contracting documents tell a different story. Task 2 describes a systematic effort to locate UACs who are already living with sponsors, using federal databases and local police to produce enforcement packages. There is no indication in the solicitation that the effort is limited to cases involving suspected trafficking or abuse. The scope appears to cover UACs broadly.

At the same time, HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is responsible for the care and placement of unaccompanied children after they are apprehended, posted a solicitation to add 30 new secure care juvenile beds in Texas. The solicitation emphasizes urgency:

“The need is immediate, as such, a ready-site with operational ramp-up as soon as possible is desired but in no case may the ramp-up be expected to take more than 90 calendar days.”

Secure care facilities are the most restrictive placement option in the ORR system, reserved for children who pose a danger to themselves or others or have been charged with a criminal offense. The beds would serve children ages 13 to 17 in a physically secure structure with heightened staffing ratios.

Secure care facilities are the most restrictive placement option in the ORR system, reserved for children who pose a danger to themselves or others or have been charged with a criminal offense. The beds would serve children ages 13 to 17 in a physically secure structure with heightened staffing ratios. The timing of this capacity expansion, alongside the Task 2 contracting language about locating UACs and producing targeting packages, suggests ORR is preparing for increased apprehensions.

Responses to the HHS solicitation were due on Monday, December 1st, 2025.

Automating the Non-Detained Docket

Task 3 outlines the creation of an automated system to review the more than seven million non detained immigration cases in the United States. The contractor is told to identify cases near the end of the immigration “lifecycle” and flag them for enforcement by field offices and 287(g) partners.

This aligns with a separate solicitation for skip tracing services which ICE describes as necessary to verify addresses and locate non detained individuals. Taken together, these two efforts form a pipeline. First, automation identifies removable individuals. Next, skip tracing teams confirm their locations. Finally, local law enforcement partners carry out the encounter.

Intelligence Intake and Remote Customer Service

DHS also posted a forecast for expanded contractor staffing for the ICE HSI Tip Line. The document has since been removed from the DHS procurement website.

The forecast called for remote customer service representatives to handle phone and web tips around the clock. According to the original text, contractors would “provide customer service and interpersonal communication skills to support the ICE law enforcement mission” and “review, analyze, and process tips for further action.” Tips are defined as “information received alleging criminal or suspicious activity within the Department of Homeland Security mission and jurisdiction in the United States and abroad.”

The setup feeds new enforcement leads into the system continuously, drawn from both public reports and local police referrals.

An Expanding Network of States

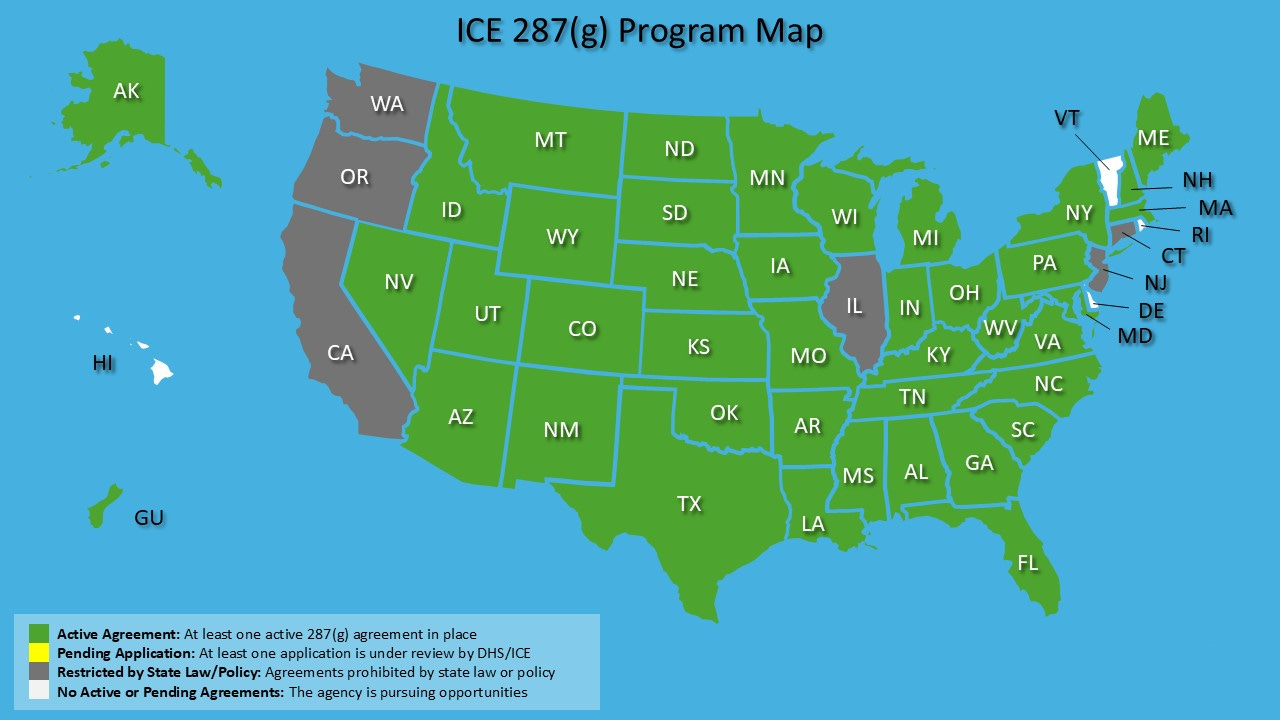

ICE currently has 287(g) partnerships with more than 1,188 police departments in 40 states and Guam — 1,053 were signed in calendar year 2025 alone. Only one of those was established prior to Donald Trump’s inauguration in January.

According to a benefit sheet posted on the agency’s 287(g) webpage, any police department that signs a Task Force Model agreement before October 1, 2025, receives a package of reimbursements: seven thousand five hundred dollars for equipment for each trained task force officer, one hundred thousand dollars for new vehicles, full salary and benefits reimbursement for trained officers, and overtime funding worth up to a quarter of an officer’s annual pay. These are significant financial rewards for departments that agree to federal deputization.

Viewed together, the full scope of the 287(g) partnership expansion is clear. The solicitations describe centralized enforcement support, heavy reliance on contractors to review and triage cases, expanded juvenile detention capacity, automated systems that surface individuals for removal, skip tracing services to find non detained immigrants, and surge staffing for large scale operations. The rapid growth of police partnerships provides the local infrastructure needed to act on all of that information.

The combined effect is a national enforcement system that runs continuously, draws local police into federal operations through reimbursement and equipment funding, and depends on contractors to keep the machinery moving.