What Is an ICE Processing Center?

A Guide to Immigration Detention Facilities and the Companies That Run Them

As Immigration and Customs Enforcement moves to purchase warehouses across the country for conversion into detention facilities, a key question has emerged: What exactly is a processing center, and how does it differ from other types of immigration detention?

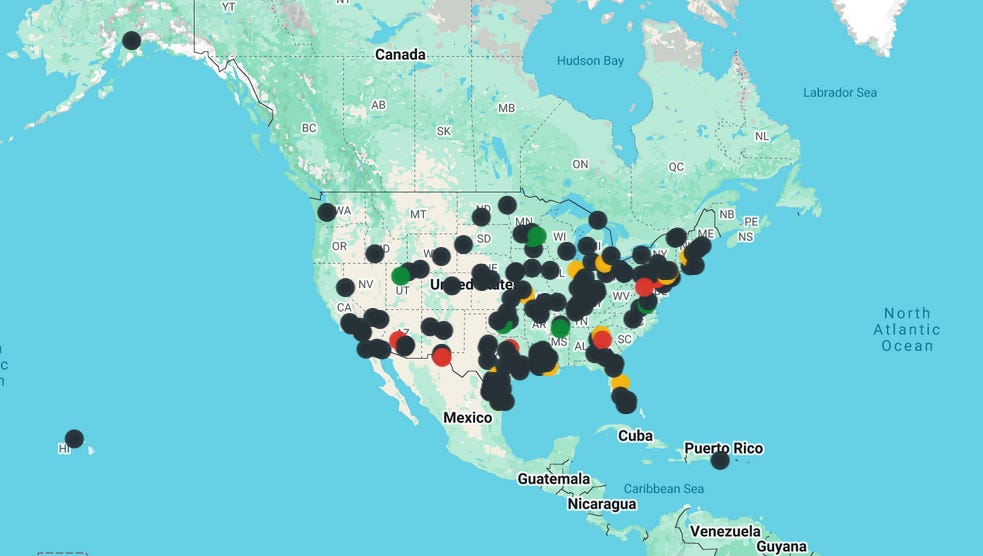

The answer reveals a vast and complex network of facilities operated through multiple types of agreements, with the majority run by for-profit contractors. With ICE detention at historic highs — approximately 70,000 people as of early 2026 — and Congress allocating $45 billion for expansion, understanding this system has never been more important.

Understanding this system — from the technical distinctions between facility types to the financial incentives driving expansion to the companies tasked with investigating abuses and deaths — is essential for anyone covering or advocating around immigration policy.

What Is a Processing Center?

An ICE processing center holds immigrants awaiting immigration proceedings or deportation. ICE operates several types of facilities based on ownership and services provided.

Service Processing Centers (SPCs) are ICE’s flagship detention facilities. ICE owns eight SPCs in locations including Batavia, N.Y.; El Centro, Calif.; El Paso, Texas; Florence, Ariz.; and Los Fresnos, Texas. These purpose-built facilities typically hold detainees for weeks or months during court proceedings.

Recent proposals to convert warehouses into detention facilities—including a 1,500-bed facility in Oklahoma City—would likely become SPCs or Contract Detention Facilities depending on ownership structure. These conversions would retrofit existing commercial buildings with holding cells, processing spaces, medical facilities, and support amenities.

How ICE Acquires Detention Space

ICE uses three primary mechanisms to secure detention capacity, each with different levels of oversight and procurement requirements:

1. Contract Detention Facilities (CDFs)

These are facilities owned and operated by private companies and contracted directly by ICE to exclusively hold immigration detainees. CDFs must go through federal procurement processes and are subject to competitive bidding requirements. Major examples include GEO Group’s Adelanto facility in California and CoreCivic’s operations across multiple states.

2. Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGSAs)

IGSAs are agreements between ICE and state or local government entities to use space in county jails or state facilities. These arrangements have become controversial because they often function as “pass-through” contracts that allow local governments to act as intermediaries between ICE and private prison companies, potentially circumventing federal procurement laws.

A 2021 Government Accountability Office investigation found that ICE uses IGSAs intentionally to bypass stricter procurement requirements that govern direct contracts with private companies. Officials told GAO that IGSAs offer “several benefits over contracts, including fewer requirements for documentation or competition.”

IGSAs come in two forms:

Non-Dedicated IGSAs house both ICE detainees and other populations (such as county jail inmates) in the same facility. The majority of immigrants in ICE custody are held in county jails under these agreements.

Dedicated IGSAs (DIGSAs) are facilities operated exclusively under agreement with ICE to hold only immigration detainees, often with a local government as the contracting party but a private company as the actual operator.

One egregious example highlighted by investigators involved the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas. The city of Eloy, Arizona — 900 miles away — collected over $400,000 annually through an IGSA while CoreCivic operated the facility and received $261 million from 2014 to 2016.

3. U.S. Marshals Service “Riders”

ICE can also place “riders” on existing contracts between the U.S. Marshals Service and detention facilities. This mechanism allows ICE to acquire detention space quickly with even fewer barriers than direct contracts or IGSAs, essentially piggybacking on another agency’s agreements.

A Model for Warehouse-Based Processing: The Ursula Facility

The clearest example of what ICE’s proposed warehouse conversions might look like already exists in McAllen, Texas. The Central Processing Center, colloquially known as “Ursula” for the name of the street on which it sits, is a retrofitted warehouse that opened in 2014 at 3700 W. Ursula Avenue. Originally a 77,000-square-foot commercial warehouse, the facility was leased by the federal government and converted to hold more than 1,000 people. The building’s layout mirrors what ICE is now proposing elsewhere: a cavernous warehouse with exposed silver piping running beneath the ceiling, divided into two main areas: 22,000 square feet for intake, processing, and adult detention, and 55,000 square feet where families and unaccompanied children are held after processing.

The facility gained international notoriety in 2018 when reporters discovered hundreds of children being held in chain-link enclosures — described by witnesses as resembling “dog kennels” or batting cages — during the Trump administration’s family separation policy. Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley, who toured the facility, reported parents being told separations would be brief, but “the reality is it’s very hard for the parents to know where their kids are.”

When the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General visited Ursula in June 2018, shortly after the Zero Tolerance policy’s implementation, investigators documented serious failures in the government’s family separation process. Although DHS had publicly claimed to have a “central database” for tracking separated families, immigration officials involved in reunification were unaware of such a system — only of a manually compiled spreadsheet that wasn’t even created until after DHS had publicly announced its existence. The OIG team also found that detained parents at nearby Port Isabel Detention Center either had never seen the informational flyers meant to help them locate their children or received them only after being separated.

A doctor who visited following a flu outbreak wrote that conditions “could be compared to torture facilities.” Ursula closed for renovations in October 2020, with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers overseeing a $30 million modernization that removed the chain-link cages, installed permanent HVAC systems, improved shower facilities, and added medical screening areas and phone lines. The renovated facility reopened in late 2021 with a capacity of 1,200. Ursula’s transformation from commercial warehouse to detention center — and the conditions documented there — offers a preview of what similar conversions might produce nationwide as ICE pursues its expansion strategy.

The Private Prison Industry Behind ICE Detention

As of 2025, approximately 86-90% of ICE detainees are held in privately operated facilities. The detention system represents a multi-billion-dollar industry dominated by a handful of major contractors:

CoreCivic

The nation’s largest private prison operator reported $538.2 million in second-quarter 2025 revenue, up nearly 10% from the previous year. CoreCivic has told investors it expects ICE contracts to generate over $1 billion in revenue in 2025 alone. The company has reactivated multiple shuttered facilities, including the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley (2,400 beds), California City Immigration Processing Center (2,560 beds), and has informed ICE it has approximately 30,000 additional beds available across idle facilities and expansion capacity.

CoreCivic’s CEO Damon Hininger told investors in August 2025: ‘I have worked at CoreCivic for 32 years, and this is truly one of the most exciting periods in my career with the company.’

The GEO Group

ICE’s largest single contractor, GEO Group reported second-quarter 2025 revenue of $636.2 million, up 5% from the previous year. Since January 2025, the company has reactivated four facilities totaling 6,600 beds, which are expected to generate more than $240 million annually. Like CoreCivic, GEO Group expects ICE contracts to generate over $1 billion in 2025 revenue and has advertised nearly 6,000 idle beds available for immediate use.

GEO Group operates some of ICE’s most prominent facilities, including the Delaney Hall detention center in Newark, New Jersey, which reopened in 2025 under a 15-year, $1 billion contract and can hold approximately 1,000 people. CEO J. David Donahue told investors the company is ‘very excited to support the mission at hand.’

Akima/NANA Regional Corporation

Akima, a subsidiary of Alaska Native corporation NANA Regional Corp., has become ICE’s largest recipient of contracts issued under the federal 8(a) program for disadvantaged businesses, accounting for nearly 60% of ICE’s set-aside contracts in that program over the past decade. Akima provides security and operational services at multiple ICE facilities, including the controversial Buffalo (Batavia) Service Processing Center in New York and facilities in Florida and Texas.

NANA’s ICE contracts approached $300 million in value in 2025, an increase of about $100 million over 2024. The company’s involvement has sparked internal controversy, with some of NANA’s 15,000 Iñupiaq shareholders questioning whether the work aligns with Indigenous values. Federal inspection reports have documented Akima guards using pepper spray and force unnecessarily, and detainees being held in solitary confinement for an average of 25 days at Batavia — 10 days longer than what New York state considers torture.

LaSalle Corrections

A Louisiana-based company that ICE has described as “an important part” of its detention operations. LaSalle manages 18 facilities and has faced congressional scrutiny over conditions at its detention centers, including allegations of medical neglect and excessive use of pepper spray on detainees.

Management & Training Corporation (MTC)

The third-largest private corrections operator in the U.S., MTC operates ICE facilities including the Otero County Processing Center in New Mexico, the Imperial Regional Detention Facility in California, and several facilities in Texas. The company has been expanding its ICE footprint, recently acquiring the former Marana Community Correctional Treatment Facility in Arizona for potential conversion to immigration detention.

The Economics of Detention

The expansion of immigration detention has created unprecedented profit opportunities for private contractors. Both CoreCivic and GEO Group saw their stock prices jump by double digits the day after the 2024 presidential election. Since then, stock prices have risen 56% and 73% respectively, with an additional 3% bump after Congress passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act allocating $45 billion for ICE expansion.

These companies and their executives donated nearly $2.8 million combined to Trump’s 2024 campaign and inaugural fund. CoreCivic’s CEO contributed $816,600 total, while GEO Group’s PAC and executives contributed nearly $2 million.

ICE contracts increasingly include guaranteed minimum payments, meaning the agency pays for a fixed number of beds regardless of whether they are used. In May 2020, ICE spent $20.5 million for over 12,000 unused beds per day on average. These guaranteed minimums ensure steady revenue for contractors even when detention populations fluctuate.

Oversight, Accountability, and Death Investigations

The rapid expansion of detention capacity has occurred alongside significant reductions in oversight. The number of ICE detention facility inspection reports dropped 36.25% in 2025 compared to 2024, even as detention rates and deaths in custody surged.

ICE is supposed to conduct inspections twice per year for facilities with an average daily population of 10 or more. However, reports on ICE’s website do not indicate that more than one inspection was conducted at any facility in 2025. Facilities that fail two consecutive inspections are required to lose federal funding, but this enforcement mechanism has rarely been applied.

Nakamoto Group and Creative Corrections

Two private companies have been responsible for conducting ICE facility inspections and investigating conditions that have led to detainee deaths.

Nakamoto Group, owned by Jennifer Nakamoto and headquartered in Jefferson, Md., has held ICE’s primary inspection contract since 2007, receiving more than $69 million in contracts in ICE contracts. Their final contract with ICE, which ended on Jan. 28, 2026, was for $1.5 million.

A Project on Government Oversight (POGO) investigation documented numerous cases where Nakamoto inspectors gave passing grades to facilities that other federal investigators found had serious, life-threatening deficiencies. At Aurora Contract Detention Center in Colorado, Nakamoto found full compliance with 41 of 41 standards just months after a detainee, Kamyar Samimi, died from inadequate medical care. The internal ICE death review found staff had failed to administer medication and delayed emergency treatment.

At Adelanto Detention Facility in California, DHS inspector general found braided bedsheets (used as nooses), seriously inadequate medical care, and improper use of solitary confinement in September 2018. Weeks later, Nakamoto inspectors found the facility in compliance with 40 of 40 standards. At Stewart Detention Center in Georgia, where two detainees died by suicide following inadequate mental health care, Nakamoto gave passing grades in both 2017 and 2018.

The company’s most controversial inspection involved Torrance County Detention Facility in New Mexico. After the facility failed one inspection in 2021, multiple subsequent reports — including from ICE’s own contracting officer and a PREA audit — found continued serious violations. Yet Nakamoto gave Torrance a ‘meets standards’ grade in March 2022. Five months later, Kesley Vial, a 23-year-old Brazilian man, died at the facility. An ICE review found the same failures identified earlier had contributed to his death.

The Nakamoto Group extended its controversial oversight role beyond traditional ICE facility inspections to managing attorney access at Florida’s ‘Alligator Alcatraz’ — a state-run immigration detention center built in 2025 on a remote airstrip in the Everglades. Court documents reveal that the DeSantis administration contracted Nakamoto to coordinate in-person and video meetings between detained immigrants and their lawyers at the facility, which has been plagued by allegations of constitutional rights violations since opening in July 2025.

Immigration attorneys have testified in federal court that detainees were forced to write their lawyers’ phone numbers on bunks and walls using bars of soap because they were denied pens and paper, that phones would cut off calls at the mention of an attorney, and that detainees disappeared from ICE’s online tracking database. Mark Saunders, a Nakamoto vice president, defended the company’s work by claiming that policies containing falsehoods — including references to a non-existent Nakamoto legal team — were simply “written rather quickly” and have since been corrected.

When Congress investigated the company’s record, Jennifer Nakamoto defended her work by invoking her family’s incarceration in Japanese American internment camps during World War II, stating her mother was born in a camp. Japanese American activists condemned this as a ‘disgusting’ manipulation of community history and held protests outside Nakamoto’s offices demanding she end her ICE contract. No Nakamoto inspection reports have been published since 2022.

Creative Corrections LLC, headquartered in Beaumont, Texas, and owned by Percy Pitzer and Stephen Spaulding, now provides inspection and investigation services to ICE’s Office of Professional Responsibility and Office of Detention Oversight (OPR/ODO). The company conducts inspections, civil rights investigations, detainee death reviews (DDRs), and investigates detention-related allegations. Since 2012, Creative Corrections has received nearly $72 million in ICE awards.

Creative Corrections achieved ISO 17020-2012 international accreditation in 2024 and claims to have completed over 1,800 audits. The company provides ‘expert operational, analytical and administrative support’ for ICE’s investigations into whether facilities comply with detention standards. However, as with Nakamoto before it, the company’s effectiveness — and ICE’s use of their findings — has come under scrutiny given the record number of deaths in ICE custody: 38 deaths from January 2025 through early February 2026, making 2025 the deadliest year on record.

Of the 38 people who died in ICE custody during this period, 71% were held in for-profit facilities, according to data compiled by lawyer and journalist Andrew Free. Deaths at Camp East Montana at Fort Bliss in El Paso have been particularly troubling. Geraldo Lunas Campos, a 55-year-old Cuban immigrant, died in January 2026 in an incident ruled a homicide by the El Paso medical examiner, with cause of death listed as asphyxia. A witness told reporters that Lunas Campos was handcuffed while at least five guards held him down and one put an arm around his neck.

Critics describe ICE’s oversight system as a “theater of compliance” designed to cover up abuses rather than correct them. In March 2025, the Department of Homeland Security made sweeping cuts to the divisions that oversee conditions in ICE facilities, further limiting accountability.

The Future of ICE Detention

With Congress having allocated $45 billion over four years for detention expansion — in addition to ICE’s regular annual budget — the agency is planning for dramatic growth. Acting ICE Director Todd Lyons told attendees at the 2025 Border Security Expo that he wants the agency to become as efficient at deporting immigrants as Amazon is at delivering packages.

“We need to get better at treating this like a business,” Lyons said, describing his ideal deportation process as “like Prime, but with human beings.”

The administration’s border adviser, Tom Homan, has called for boosting ICE’s detention capacity to at least 100,000 people. To achieve this, ICE is pursuing multiple strategies: converting warehouses into processing centers, reopening shuttered prisons (at least 16 facilities across a dozen states have reopened since January 2025), and signing new contracts with private operators.

Some communities have pushed back against these plans. Newark, N.J.’s mayor rallied protesters outside the reopened Delaney Hall facility. Leavenworth, Kan., sued CoreCivic over reopening a facility there. And local officials in communities identified for potential warehouse conversions have raised concerns about infrastructure impacts, from water supply to emergency services.

Yet the expansion continues, creating what immigration scholars describe as an infrastructure that will be difficult to dismantle even if future administrations seek to wind down mass detention. The combination of guaranteed minimum payments, long-term contracts (often 10-15 years), and the economic interests of communities that benefit from detention facilities creates powerful incentives to maintain the system.

As CoreCivic’s then-CEO put it in August 2025: “Our business is perfectly aligned with the demands of this moment. We are in an unprecedented environment with rapid increases in federal detention populations nationwide and a continuing need for solutions we provide.”

One thing people do not realize is that warehouses are designed with toilet and plumbing facilities for very few occupants. The water and sewer utilities are grossly undersized for this purpose, not to mention that there are many other code differences between these facility types (Industrial vs Residential). It is highly doubtful that the modifications required to bring them into compliance with building codes are being done as the federal government claims exemption from those. They purposely treat these poor people worse than animals. It might be successful in deterring more immigrants, but it is evil, despicable and depraved, just like Trump, Noem and Homan.

Thank you for your excellent reporting. The research and writing is top notch. If I can ever be of help with fact-checking, copy editing, or proofreading (not that your posts show you need this; I'm just volunteering to help out) let me know. I'm a former journalist and freelance writer. In Maryland I'm proud that a bill is advancing in the General Assembly to outlaw 287 agreements between local law enforcement agencies and ICE.